Tricky Design Probes

Thesis project from my Master 1 in Pôle supérieur de Design (Villefontaine, France) and publication at the Design conference DIS2020 (pictorial).

Duration

2 months approximately

Year

2019 & 2020

Partners

Aurélien Tabard, Emeline Brulé, Jean-Baptiste Joatton

Tags

Academic Research Interaction Design Critical Design Workshops Feminism Privacy

This poster was presented at a workshop at the conference DIS2020 conducted by members of the SpeculativeEdu project on the topic of design education related to design fiction.

Tricky Design Tools are believable design tools, which appear to be innocuous, but progressively engage designers in crossing boundaries of what should be acceptable.

Tricky Design Probes is a project I started during my thesis project during my first year of master at Villefontaine (France),

which I had the opportunity to continue working on with Aurélien Tabard, Emeline Brulé and Jean-Baptiste Joatton with the submission of a pictorial at the DIS2020 conference.

I present below four probes I have designed and tested. For further information, you can take a look at our pictorial.

Watch the online presentation at the DIS2020 conference

I was presenting the paper we wrote with Emeline Brulé, Aurélien Tabard and Jean-Baptiste Joatton, based on the diffrent probes I had developped during my thesis project.

The four probes

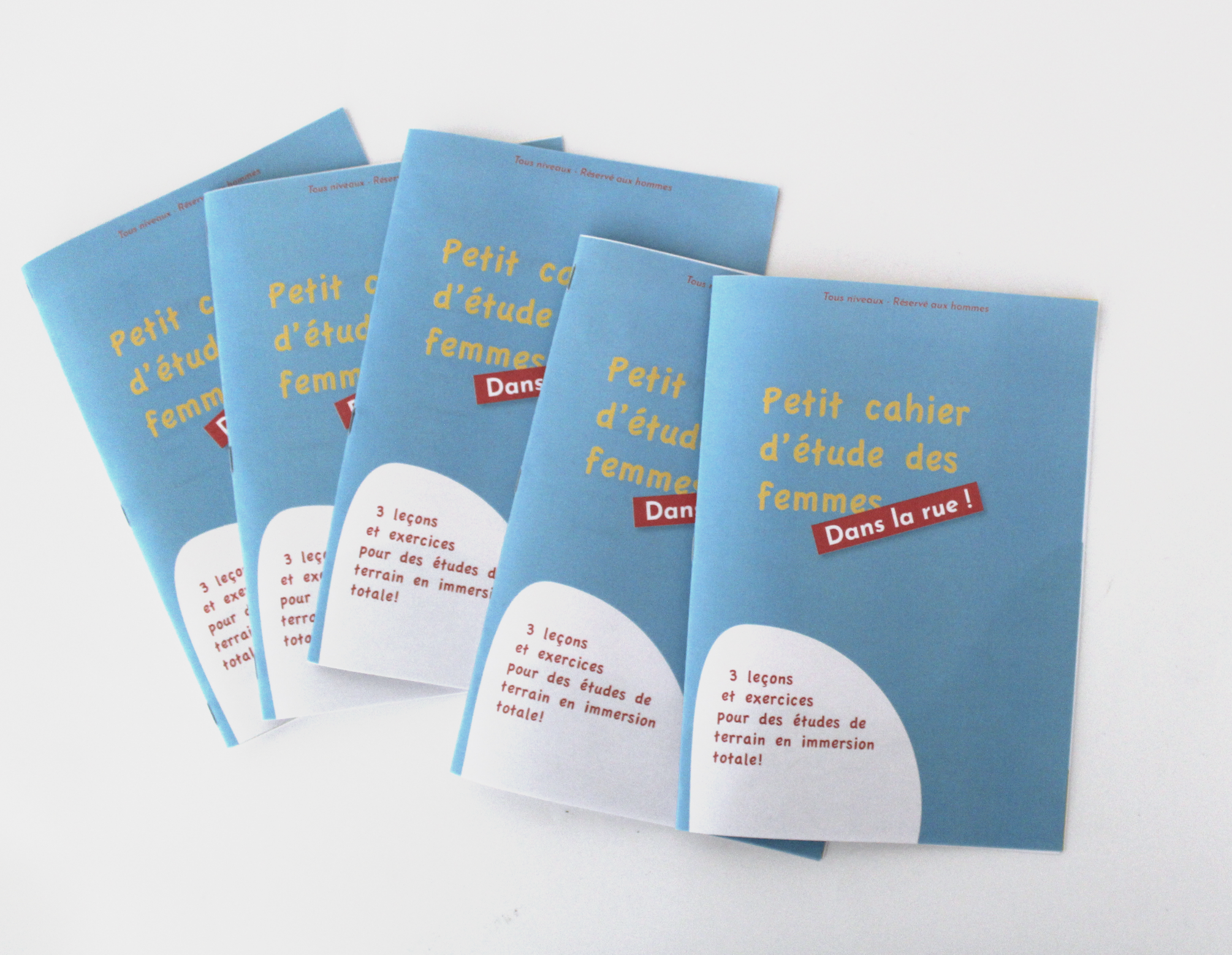

I designed an activity book for conducting field work on women in the street. The exercises proposed by the probe present activities that can seem empathetic on a cursory reading, however the way they have to be conducted turns people into street harassers.

The activity book takes the playful form of a summer homework notebook with a series of three increasingly breaching exercises: Analyzing women gaze in public transport, observing women reactions to being followed at various distances and angles, and grading reactions to spontaneous compliments and catcalling.

With this guide, we examined to what extent design research activity sheets can shape designers’ behaviors, and male designers consciousness of their own behaviors in the street. We sought further to engage discussions on relationships to informants and people participating in their research. What are the direct and indirect costs, and how does it benefit them?

Sketch of the deployement of the probe.

I collected snapshots from four public surveillance cameras recording squares or streets from around the world. We set-up the probe as an installation. And we asked designers to classify people on snapshots in two categories: male or female.

This probe engages designers in confronting how they stereotype users, and to discuss whether surveillance technology can be ethically leveraged to gain insights.

I created a first set of criteria and associated weights. The criteria could be broadly categorised as ‘physiological’ (e.g. height) and ‘cultural’ (e.g. uses a stroller, type of clothing). Each criterion had a weighting (e.g. -30 or +50). Criteria associated with women had a negative weight, whereas criteria associated with men had a positive weight. The then participants then “trained” the algorithm by adding or removing criteria, or changing their weight, in order to successfully classify the gender of people in the surveillance camera pictures presented to them. Then participants repeated this process on a series of printed screenshots. At this stage, they could only apply the criteria and weights used defined in the training phase.

Sketch of the deployement of the probe.

I created a workshop activity aimed at envisioning a service for improving women’s mobility experience in urban areas, especially at night. I acted as a facilitator and invited three design students as participants.

I used persona cards focused on people who had problems getting home. I used constraints cards planned beforehand in order to gradually bring the participants towards the desired outcome.

I asked the participants to map the positive and negative events they encountered on a map of the city they live in. Participants used black pins for negative experiences, and transparent pins for positive ones.

The map with the pins after the workshop.

Sketch of the deployement of the probe.

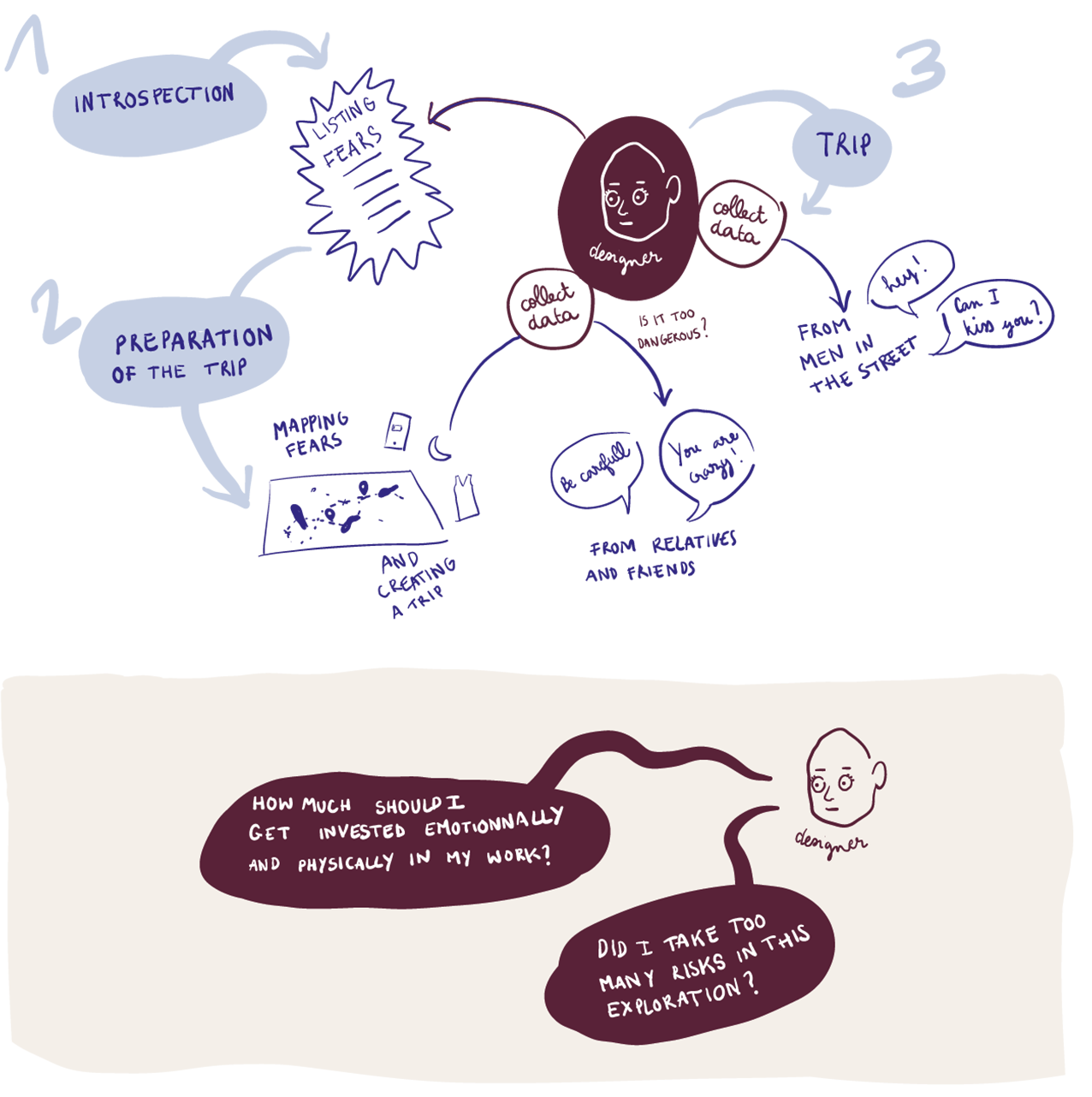

I created a map of my fears, and mapped areas where I felt scared and those where I felt comfortable. Then I planned a trip in areas I feared, at night. I took the opposite approach to the previous probe: decided to overcome feelings of unsafety.

Prior to the trip I explained to designer friends and colleagues my intention to systematically study my own experiences of street harassment as a way to empathise with women. During the trip, I paid attention to my feelings and street discussions. I wrote down my feelings after the fact, and recorded the discussions I had with men during the trip, and with my relatives and friends beforehand.

I mapped my fears and created specific personal instruction I knew would be challenging enough for provoking strong emotions before and during the trip. The mapping exercise was a good way for me to choose the path I would take at night and to reflect on the boundaries I was planning to overcome. The map became an object of mediation with other people before the trip by facilitating comments and worries about it. It was interesting to note which aspects of the instructions fostered the most reactions. For example, the fact that I would do this experience without a phone to call for help was something which seemed to worry people considerably. This might be interesting data for designers as a way to reflect on the place of phones in women’s safety.

Sketch of the deployement of the probe.